When the New Year started in 2014, I’d wanted to honor a Kindle tradition I started nearly four years ago. It’s remembering one of my favorite memories about books, a special moment when time itself seemed to magically turn into something that you could hold in your hands. It gave me a feeling that I’ll never forget about books…and about the authors who write them. And for a second “history” seemed to be another word for a special glow that you could actually feel…

And it also led to a few fun free Kindle ebooks!

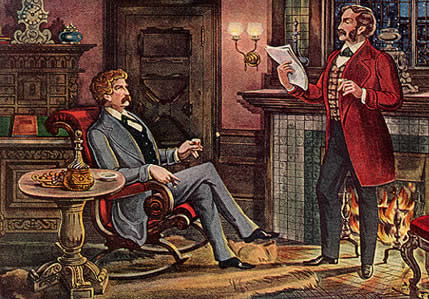

This adventure all started a few years ago, when I was surfing the web and discovered that Mark Twain had once co-authored a play with a forgotten writer named Bret Harte. (Once their legendary meeting was even depicted in the ad for Old Crow whiskey pictured above). Here’s how Twain himself described it.

“Well, Bret came down to Hartford and we talked it over, and then Bret wrote it while I played billiards, but of course I had to go over it to get the dialect right. Bret never did know anything about dialect…”

In fact, “They both worked on the play, and worked hard,” according to Twain’s literary executor. One night Harte apparently even stayed up until dawn at Twain’s house to write a different short story for another publisher. (“He asked that an open fire might be made in his room and a bottle of whiskey sent up, in case he needed something to keep him awake… At breakfast-time he appeared, fresh, rosy, and elate, with the announcement that his story was complete.”) I was delighted to discover that 134 years later, that story was still available on the Kindle, “a tale which Mark Twain always regarded as one of Harte’s very best.”

Bret Harte’s short story (as a free Kindle ebook)

Biography of Mark Twain by his executor (as a free Kindle ebook)

Right before Christmas, I wrote about how Harte’s words had already touched another famous writer — Charles Dickens. Before his death, 58-year-old Dickens had sent a letter inviting Bret Harte for a visit in England. But ironically, that letter didn’t arrive until after young Harte had already written a eulogy marking Dickens’ death. It was a poem called “Dickens in Camp,” suggesting that to the English oaks by Dickens’ grave, they should also add a spray of western pine for his fans in the lost frontier mining towns of California…

But two of Harte’s famous short stories had already captured Dickens’ attention — “The Outcasts of Poker Flat” and “The Luck of Roaring Camp.” John Forster, who was Dickens’ biographer, remembers that “he had found such subtle strokes of character as he had not anywhere else in later years discovered… I have rarely known him more honestly moved.” In fact, Dickens even felt that Harte’s style was similar to his own, “the manner resembling himself but the matter fresh to a degree that had surprised him.”

The Luck of Roaring Camp and other stories

Forster’s Life of Charles Dickens (Kindle ebook)

So on one chilly November afternoon, I’d finally pulled down a dusty volume of Bret Harte stories from a shelf at my local public library. I’d had an emotional reaction to “The Outcasts of Poker Flats” — and an equally intense response to “The Luck of Roaring Camp.” But Harte’s career had peaked early, and it seems like he spent his remaining decades just trying to recapture his early success. (“His last letters are full of his worries over money,” notes The Anthology of American Literature, along with “self-pitying complaints about his health, and a grieving awareness of a wasted talent.”) Even in the 20th century, his earliest stories still remained popular as a source of frontier fiction — several were later adapted into western movies. But Harte never really achieved a hallowed place at the top of the literary canon.

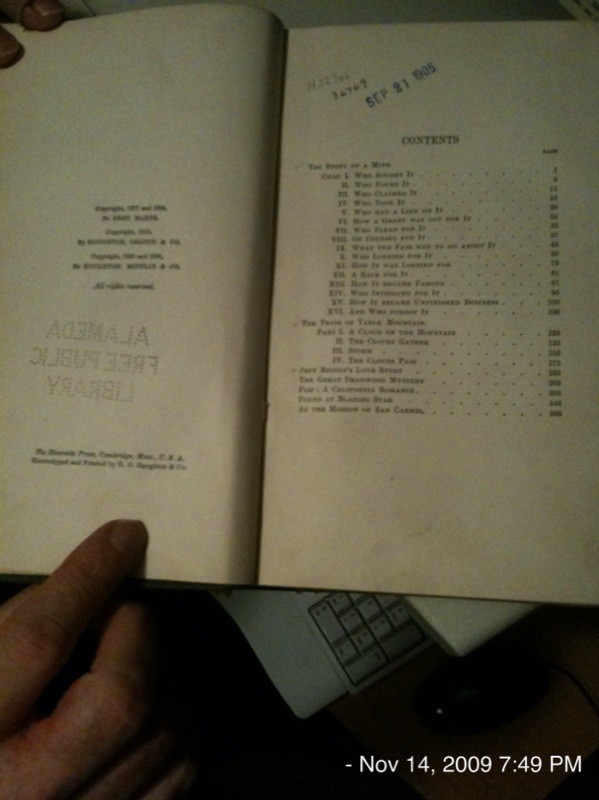

Yet “The Luck of Roaring Camp” ultimately became the very first ebook that I’d ever ordered on my Kindle. (I’d been looking for print editions, but hadn’t found a single one at either Borders, Barnes and Noble, or a local chain called Bookstores, Inc.) It was several days later that I’d decided to try my public library, where I discovered a whole shelf of the overlooked novelist (including an obscure later novel called The Story of a Mine). And that’s when I noticed the date that the library had stamped on its inside cover.

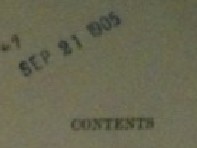

“SEP 21 1905.”

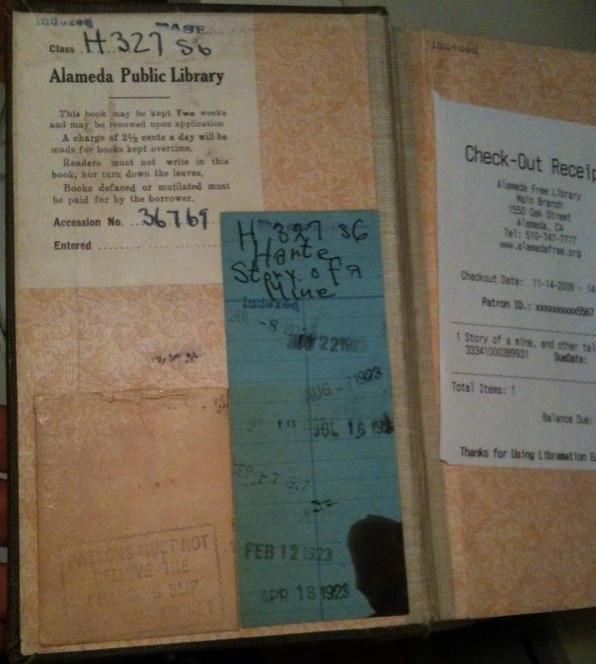

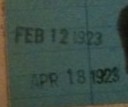

I felt like I was holding history in my hand. The book was published just three years after Harte’s death in 1902, and there was an old-fashioned card, in a plastic pocket glued to the inside cover, which showed some of the past check-out dates, including FEB 12 1923 and APR 8 1923.

More than a century later, my local librarians had tagged this ancient book with an RFID chip so you could check it out automatically just by running it across a scanner. A computerized printer spit out a receipt, making sure that the book wouldn’t remotely trigger their electronic security alarm when it was carried past the library’s anti-theft security gates.

I hope that somewhere, that makes Bret Harte happy.