Lately my most popular post is the one about William Saroyan — the 1940s novelist who actually turned down a Pulitzer Prize for literature. I’d called him “The Author You Can’t Read on your Kindle,” and while it’s still true, there’s something that’s almost as good. There’s a fascinating biography about Saroyan’s wild life — and the ebook’s two modern-day authors include one of my favorites.

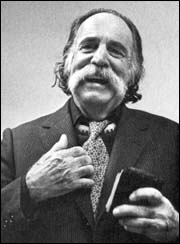

Barry Gifford wrote Wild at Heart, a story about two passionate but unlucky drifters living together on the road. David Lynch adapted it into a movie starring Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern, and when I saw Gifford speak in the early 90s, he was also working on a movie adaptation of Jack Kerouac’s On The Road. Gifford was hosting a film noir festival, arguing there was a unspeakable truth in the best of the B-movies. Gifford seemed comfortable with the grittier side of literature, and tonight I discovered he’d co-authored this detailed biography of William Saroyan.

“Along with Ernest Hemingway, William Saroyan…was the most well-known American writer of the 1930s and 1940s,” according to Amazon’s description of the book, and the two authors “heard Saroyan’s story first-hand from Carol Matthau, the wife he rejected; the son and daughter he alternately smothered and pushed away; and colleagues like Artie Shaw, Celeste Holm, and Lillian Gish.” (The Boston Herald called it a “beautifully balanced account” of the “triumphs and agonies” in the author’s life.) I think Barry Gifford understands the zest and exuberance that Saroyan brought to his work — and to his life.

And coincidentally, you also can’t read Gifford’s Wild at Heart on the Kindle either. (Though you can buy one of its sequels, The Imagination of the Heart, which Gifford published just last year at the age of 63…)

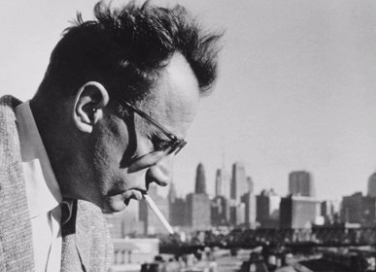

I’m excited about this book because Saroyan lived a fascinating life. As a young boy he’d lived in an Oakland orphanage, and later served in the army during World War II at the peak of his writing career. (It was just two years after he’d declined the Pulitzer Prize, and two years before his Academy Award for Best Writing, Original Story.) According to Wikipedia he “worked rapidly, hardly editing his text, and drinking and gambling away much of his earnings.” And if that weren’t enough, he “narrowly avoided a court martial when his novel The Adventures of Wesley Jackson was seen as advocating pacifism!”

In February, I’d worried that “he’ll be one of those authors who won’t transition into the next generation of media. In our shiny future, we’ll have expensive ‘readers’ with fancy new features — but with a couple of last-century authors who somehow just didn’t make the cut.” So I always get a warm feeling when the digital world finds its way to a little bit of Saroyan. Maybe instead of talking about the man, or his biography, or his biographer, I should just share his advice to young writers of the future.

“Try to learn to breathe deeply; really to taste food when you eat, and when you sleep really to sleep. Try as much as possible to be wholly alive with all your might, and when you laugh, laugh like hell.”