Last week in Seattle, Amazon held their annual shareholder’s meeting, and since it was also being web-cast I decided to sneak a listen. One of the very first things on the agenda was a shareholder’s request that Amazon report on how it’s handling climate change — how Amazon assesses its own impact through the release of greenhouse-gas emissions. And specifically: the environmental impact of the Kindle…

The measure was voted down — the same shareholders have apparently made the same request every year for the last five years — but I was surprised by one of the statistics they cited. “70% of S&P 500 companies and over 80% of Global 500 companies disclose this type of information through the Carbon Disclosure Project, including companies such as Google, eBay, Apple, and Target.” But it turns out Amazon’s CEO had already included some environmental information in his prepared remarks.

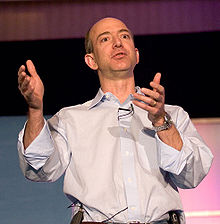

Jeff Bezos took the podium, and proudly talked about how Amazon had launched their “frustration-free packaging initiative” just a few years ago, “designed to eliminate wire twist ties, blister packs, and

those clear hard plastic packages that you need a small nuclear device to open. And usually they result in bleeding.” I was surprised, but it turns out he wasn’t kidding about the bleeding. “I use to know the statistic of how many emergency room visits there are per year from people trying to open blister packs.”

But more to the point: “It’s very frustrating as a consumer.”

And then Jeff Bezos schooled the audience, revealing the dirty secrets behind blister packs and elaborate four-color cardboard packaging. “They’re both designed for the traditional physical retail environment. The blister packs are important because you can see the product and seeing the product is part of on-shelf merchandising. And you often see small items in big blister packs. The reason that that’s done is to make shoplifting more difficult.”

“At Amazon we don’t need either of those. We don’t have either of those reasons. We get to separate the physical packaging of the item from the merchandising of the item. And we also don’t have to worry about shoplifting!”

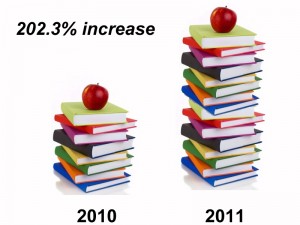

The funny thing is that according to Bezos, it’s actually more expensive for manufacturers to add blister packs — so Amazon is working with manufacturers to create a different set of packaging for online shoppers. (Otherwise, as Bezos points out, “It’s expensive for the manufacturer, it’s inconvenient for the consumer, and it’s also very wasteful from an environmental point of view.”) Since Amazon launched this program in 2008, they’ve gone from just 250,000 items in frustration-free packaging to over 4 million, Bezos told his shareholders. “And this, by the way, does not include Amazon-branded items like the Kindle or our Amazon Basics line, which are also in frustration-free packaging,” he pointed out. “These numbers only represent our efforts working together with third-party manufacturers to get them to adopt our frustration-free packaging standards.”

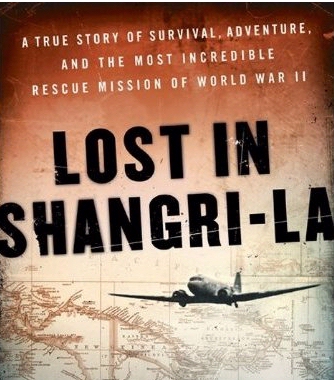

Of course, Kindle owners probably care more about the answer to a more direct question: How many e-books do I have to read before I’ve saved a tree? Last year it was the subject of an article by Geoffrey Lean, a newspaper reporter identified by the Daily Telegraph as Britain’s longest-serving environmental correspondent. (He’s been reporting on the environment for almost 40 years). Lean reported there’s two theories about whether the Kindle (and other digital readers) are environmentally-friendly.

Gadget-lovers point out that the US printed word causes 125 million trees to be felled every year. The bookish retort that the e-readers take more energy to make, consume electricity, contain more chemicals, and create a greater waste problem when thrown away.

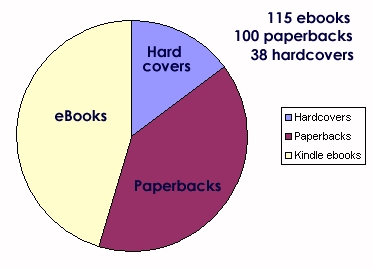

The real answer appears to hinge on how many books you read each year, Lean concludes, with different studies arriving at different answers. “One reckoned that you would have to get through 40 electronically each year to come out ahead, another made that 23, while a third concluded that the carbon produced in making each e-reader would be recovered by the trees it left standing in just 12 months.” His final answer was a little dissatisfying — that the greenest way to read “turns out to be old-fashioned. Get books – from a public library.”

And I’d argue it still remains an open question — since it still depends on how far you’ll drive to get to your public library!